Systems Engineering at NASA

October 2023

Oliver Taylor

This study attempts to summarize how NASA’s System Engineers operate in order to better understand how to manage complex technical projects.

Introduction

NASA has been successfully running some of the most expensive and complex engineering projects in history for a very long time. They explore the very edge of what is known and what is possible, their projects cost billions of dollars, their success is subject to the unforgiving demands of physics, and they are funded with tax-payer money.

Managing those projects – ensuring they accomplish their stated objectives, controlling their costs, and managing the team and schedule – is no small task, and they have gone to the trouble of documenting, in great detail, how they do it.

This study attempts to summarize how NASA’s System Engineers operate in order to better understand how to manage complex technical projects. This is a work of subjective summarization and analysis, see § References for my sources.

Defining Systems Engineering

The management of projects at NASA is divided between 3 groups of people. (1) Project Managers are responsible for the team and for the success of the project as a whole, (2) Project Planning and Control (PP&C) is responsible for identifying and controlling the cost and schedule, and (3) Systems Engineers are responsible for the conceptualization, design, and deployment of “all hardware, software, equipment, facilities, personnel, processes, and procedures” required by a project.

So the “system” which Systems Engineers engineer should be thought of as the combination of all the various tools, processes, and people which make the project possible. Everything required by the project falls under their design.

It is a way of looking at the “big picture” when making technical decisions. It is a way of achieving stakeholder functional, physical, and operational performance requirements in the intended use environment over the planned life of the system within cost, schedule, and other constraints. [NASA Systems Engineering Handbook]

A System of Products

A “product”, in the language of NASA’s systems engineers, is something that must be built. That product can either be used directly or integrated into another product. For example: a communications system is a product but so are all the component parts that make up the communications system. At the highest level the project itself can be considered a product comprised of sub-products. It is the aggregation of products that create the system. So, in this light, we can say that a Systems Engineer designs and manages the integration of discrete products into an operable system.

The Systems Engineering Engine

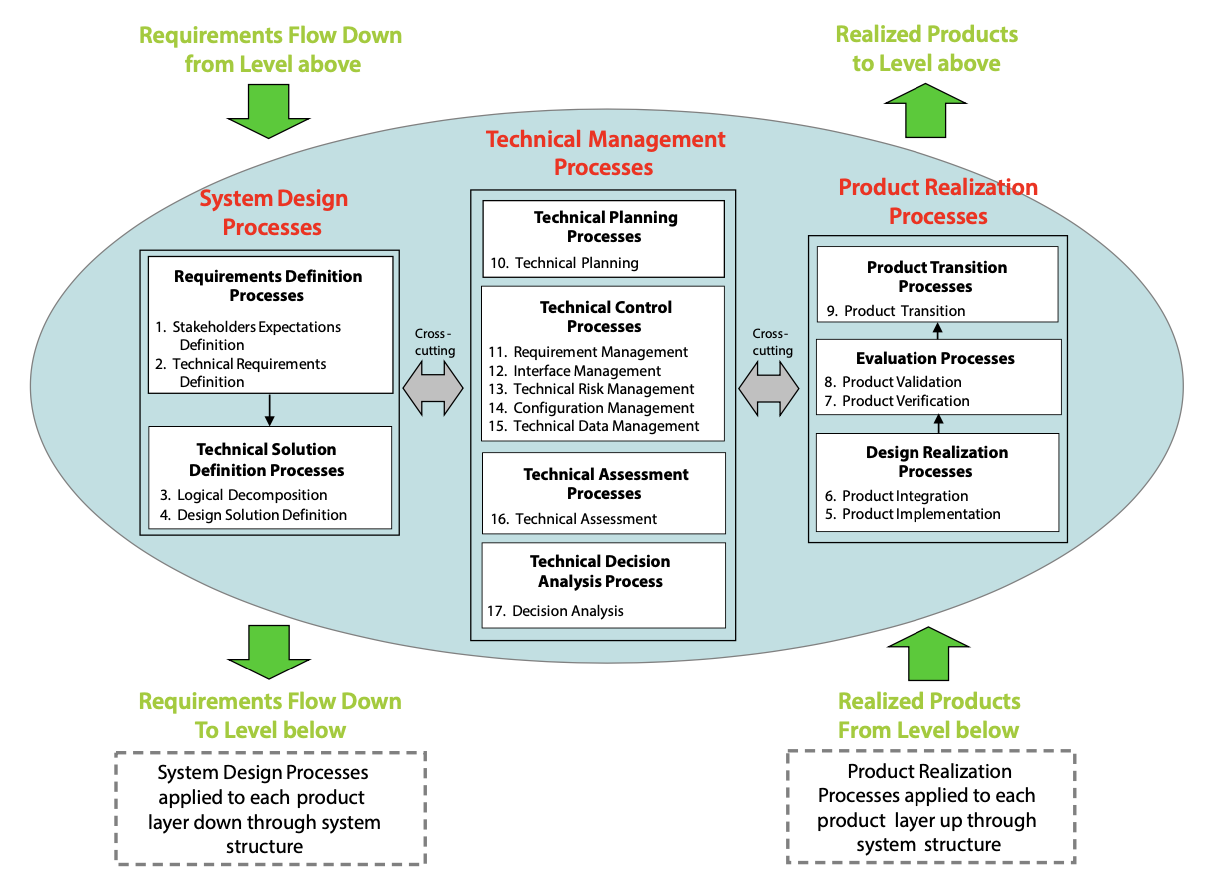

To design and build this system of products systems engineers use something called the System Engineering Engine. It is a set of activities (with very well-defined, well-documented procedures and outputs) whose purpose is to “develop and realize the end products”.

The SE Engine is a tool for defining product requirements, designing a solution for how to meet those requirements, technical planning, the creation of processes, assessment strategies, and actually doing the work of realizing the products themselves. The engine is used “both iteratively and recursively”, meaning: to each iteration of a product, and to each product within the system.

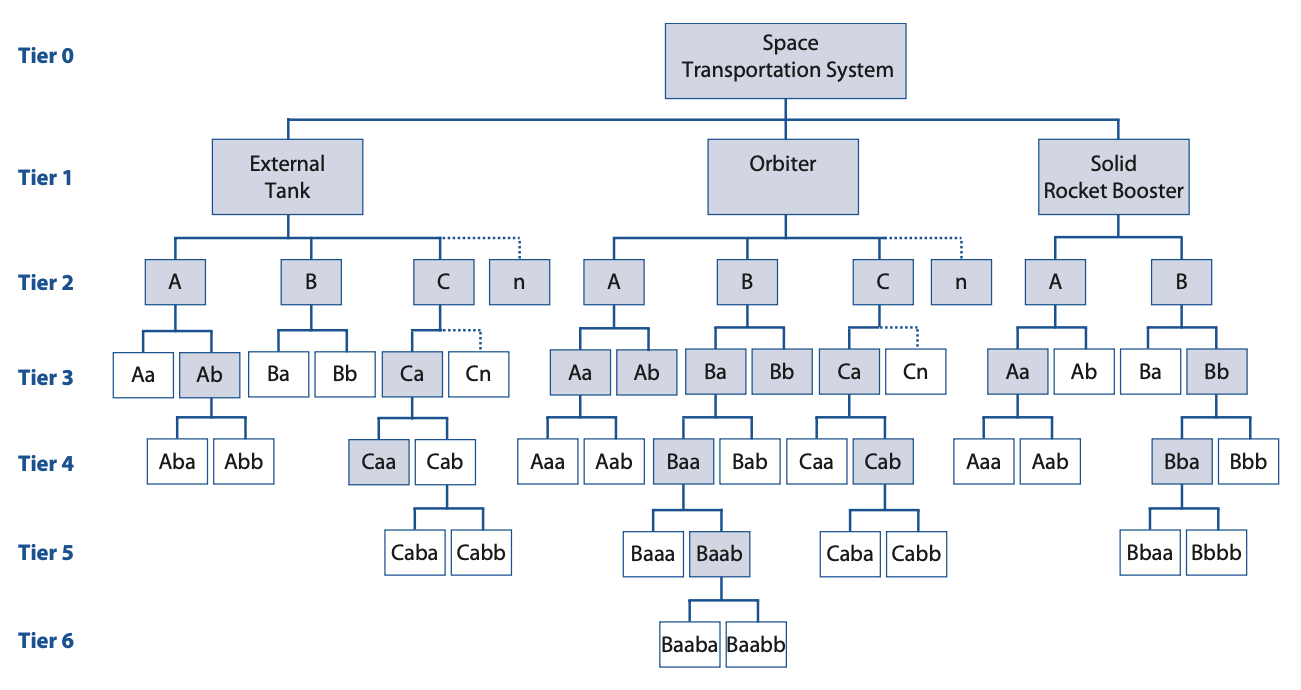

Let us imagine that NASA needs to build a “truck” to carry equipment and crew into low earth orbit. That truck, the Space Transportation System, is called the “Tier Zero” product.

Systems engineers begin by applying the SE Engine to the tier zero product, in this case the “truck”. Once you’ve done that for the tier zero product you begin doing it “recursively”, to each of the tier 1, 2, 3, etc products. Doing this builds a “product tree” that will make up the system as a whole.

The engine itself consists of 3 major steps:

Design the system • Systems engineers begin by looking at the technical requirements and stakeholder expectations for the truck. They then design a solution to meet those requirements. Then, they define the Tier 1 sub-products that need to be built, and all of their requirements.

Realize the product • They make a plan for building, buying, coding, or reusing the truck. Then they plan for testing and integrating it.

Manage the technical processes • They establish and evolve the truck’s technical plans, assessment of its performance against requirements, and they control the technical execution of the product.

Step One: System Design

The very first step in designing a system is to understand expectations:

Thoroughly understanding the customer and other key stakeholders’ expectations for the project/product is one of the most important steps in the systems engineering process. It provides the foundation upon which all other systems engineering work depends. It helps ensure that all parties are on the same page and that the product being provided will satisfy the customer. When the customer, other stakeholders, and the systems engineer mutually agree on the functions, characteristics, behaviors, appearance, and performance the product will exhibit, it sets more realistic expectations on the customer’s part and helps prevent significant requirements creep later in the life cycle. [NASA Systems Engineering Handbook]

Once expectations are understood and defined, you need to have 4 “outputs” from this design stage:

- A validated set of stakeholder expectations.

- A “Concept of Operations”, or ConOps – a document describing exactly how the system/product will be used to meet stakeholder expectations. This document describes, in detail, the exact scenarios in which the product will be used.

- An understanding of the enabling product support strategies – plans for how to make, test, deploy, operate, and dispose of what you are actually building.

- An idea of how to measure the product’s effectiveness.

Remember that all of this is done “iteratively and recursively” to every product in the product tree.

A Brief Aside: Verification & Validation

“Verification” and “Validation” have very specific meanings at NASA. Verification is when a product shows “proof of compliance with requirements”. Validation is when a product shows “the product accomplishes the intended purpose in the intended environment”.

Products that meet requirements but fail to have the intended effect on the system (verified but not validated) are particularly problematic because this usually means the deficient product must be reengineered late in the project’s life cycle, which can lead to schedule delays and budget overruns – and, most critically, the potential need to compromise some aspect of the project to prevent those budget and schedule overruns.

NASA’s primary tool for preventing validation failures is the development of a robust ConOps in the early phase of the project. “Frequent and iterative communications with stakeholders helps to identify operational scenarios and key needs that should be understood when designing and implementing the end product.” [NASA Systems Engineering Handbook]

Step Two: Product Realization

Realizing, or actually building, the required product can be thought of as a three step process:

- Realize the design. This can mean making or coding it, reusing something that’s already been built, or simply buying it off the shelf.

- Verify and validate the product.

- Transition the product. Deliver the product to the parent product in the product tree. It is important to note that many iterations of products are transitioned – plans and documents at first, then perhaps simulations, then preliminary test units, leading to the final product.

Step Three: Technical Management

NASA’s projects are so complex that each product should be considered its own mini project. Thus, a single product has a large variety of needs – budgeting, staffing, scheduling, integration with other teams, evaluation of risk, communications, research, equipment purchasing, vendor contracting, etc. Technical management is the task of building the machinery and team that designs and realizes each and every product, no matter how numerous or complex.

These technical management processes are described as the “bridge” between the technical and product planning and control teams – sometimes referred to as “crosscutting” functions.

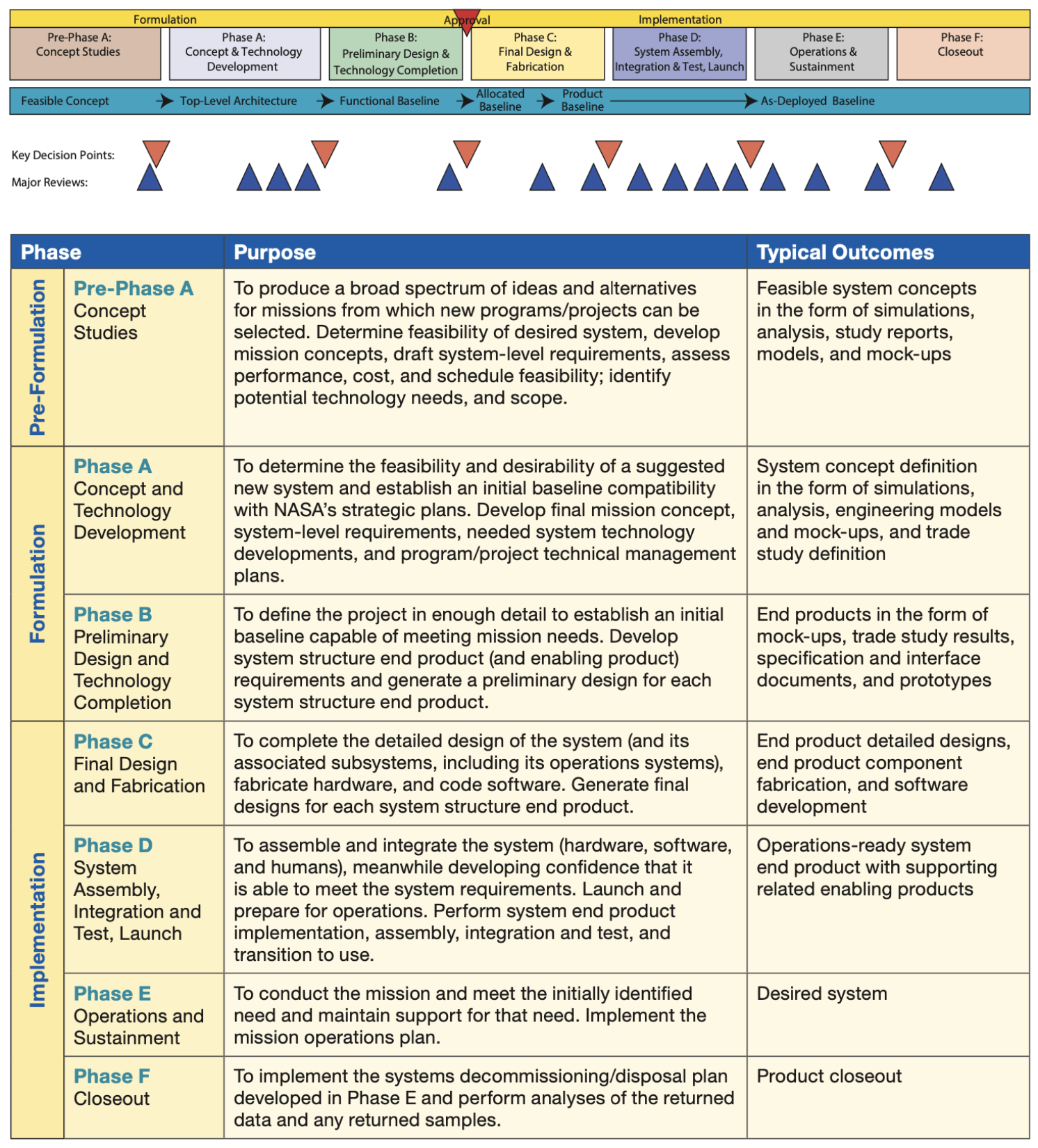

The NASA Project Life Cycle

NASA organizes each project into more manageable pieces using something they call the Project Life Cycle. Each phase of the cycle is designed to “provide managers with incremental visibility into the progress being made” and to provide opportunities between each phase to insert Key Decision Points (KDPs). KDPs are akin to tests that a project must pass before it can proceed to the next phase.

The Project Life Cycle Phases Table below outlines all the life cycle phases, the purpose of each, and typical outcomes. It is worth reading in detail.

It is interesting to note that the development of the concept and technology are each split in half, providing an additional decision point mid-way through each phase. This was done by NASA intentionally “to ensure closer management control” of the project.

At each phase in a project’s life cycle the recursive use of the SE Engine continues, fleshing out expectations and designs, the concept of operations, technical requirements, support systems, testing techniques, and management requirements.

Those interested in a more detailed breakdown of these phases, all the key decision points, typical activities in each phase, and their expected outputs, should see section 3.0 of the NASA Systems Engineering Handbook, and its expanded guidance companion.

Systems Engineers Are People Too

Processes make the complex predictable, and allows people to coordinate. Processes are descriptions of what has worked in the past. Without rigorous processes complex systems would quickly become unmanageable, and catastrophic problems far more likely.

If, as Thomas Edison said, “success is 10% inspiration and 90% perspiration”, at NASA the design of the system is the inspiration and the rigorous application of process is the perspiration.

No matter how brilliant the design, we must still understand and properly apply rigorous processes and procedures throughout the project’s lifecycle. Otherwise, what seemed like the right design will have a high probability of failing to meet its intended mission, within cost and schedule. Systems engineers must be able to deal with broad technical issues and apply rigorous processes and procedures especially as projects get larger and more complex. [The Art and Science of Systems Engineering]

NASA advises system engineers to own the processes and tools, and not to be owned by them, because “a lack of process rigor can easily lead to disaster, but too much process rigor can lead to rigor mortis.”

But process, of course, is not everything:

Processes and tools are very important, but they can not substitute for capable people. Following processes and using tool sets will not result automatically in a good systems engineer or system design. Entering requirements into a database does not make them the right requirements. Having the spacecraft design in a computer-aided design (CAD) system does not make it the right design. Capable and well-prepared people make the difference between success and failure. [The Art and Science of Systems Engineering]

Recognizing this, NASA launched the Systems Engineering Behaviors Study, whose goal was “studying how highly regarded systems engineers at each of the ten NASA Centers practice the art of systems engineering” with an eye toward designing or updating “systems engineering training, development, coaching and mentoring programs to develop these behaviors in systems engineers. This data will also help NASA Engineering Leadership to more quickly identify and support the development of high potential future SE leaders.”

Their findings were that there is “a shared set of specific behaviors at NASA that enable individuals to excel as system engineers. These behaviors are observable and measurable. And, while these behaviors come naturally to some individuals, they are skills that potentially can be developed and learned.”

Specifically, they found:

Highly successful SEs possess a foundation of advanced technical knowledge in one or more areas. While this knowledge provides the essential footing, it is the softer, less definable skills that set these individuals apart.

Creativity, curiosity, mixed with self-confidence, persistence and a knowledge of human dynamics, allows the highly regarded SEs to be successful. They have the ability to ask the questions, identify what is missing, pinpoint the soft spots in a design, then help to identify a solution to the problem. The SEs understand what must happen to obtain success and what must happen to avert failure. They are drawn to the challenge of solving complex problems by possessing an approach that is comprehensive and intentionally does not favor any particular sub-element of a system. They look across the entire system and facilitate trades and compromises to get a balance, optimized design. They exhibit excellent human relations skills, and understand how to create a vision for the team by keeping the team on track by holding a big picture view of what needs to be accomplished in order to reach mission requirements. They clearly demonstrate the growth mindset in all its many facets. These findings are consistent with the literature on highly successful and effective people. [NASA Systems Engineering Behavior Study]

The Systems Engineering Behaviors Study provides a detailed breakdown of the specific attributes effective systems engineers possess:

Intellectual Curiosity • Systems engineers must be the curious type. They must move through the “contiguous vacua” – the connected, empty, unexplored spaces – of a project. They must “continually try to understand the what, why, and how of their jobs, as well as other disciplines and situations that other people face. They are always encountering new technologies, ideas, and challenges, so they must feel comfortable with perpetual learning”.

Ability to See the Big Picture • NASA is, essentially, trying to answer fundamental questions about the universe; so good systems engineers must be completely conversant with the questions their project is asking, and keep them in mind when designing solutions and managing trade-offs. The entire discipline of systems engineering, and the SE Engine itself, is a way of designing, constantly observing, and aligning activities to the big picture. Take, for example, the distinction between verification and validation. Tt is not enough to ask “did we build our system right?”, one must also ask “did we build the right system?”

Part of this is the ability to keep everyone on the same page. Translating objectives into terms each team member can align with is key:

Good systems engineers are able to “translate” for scientists, developers, operators, and other stakeholders. For example, “Discover and understand the relationship between newborn stars and cores of molecular clouds,” is meaningful to a scientist. But developers and operators would better understand and use this version: “Observe 1,000 stars over two years, with a repeat cycle of once every five months, using each of the four payload instruments.” [The Art and Science of Systems Engineering]

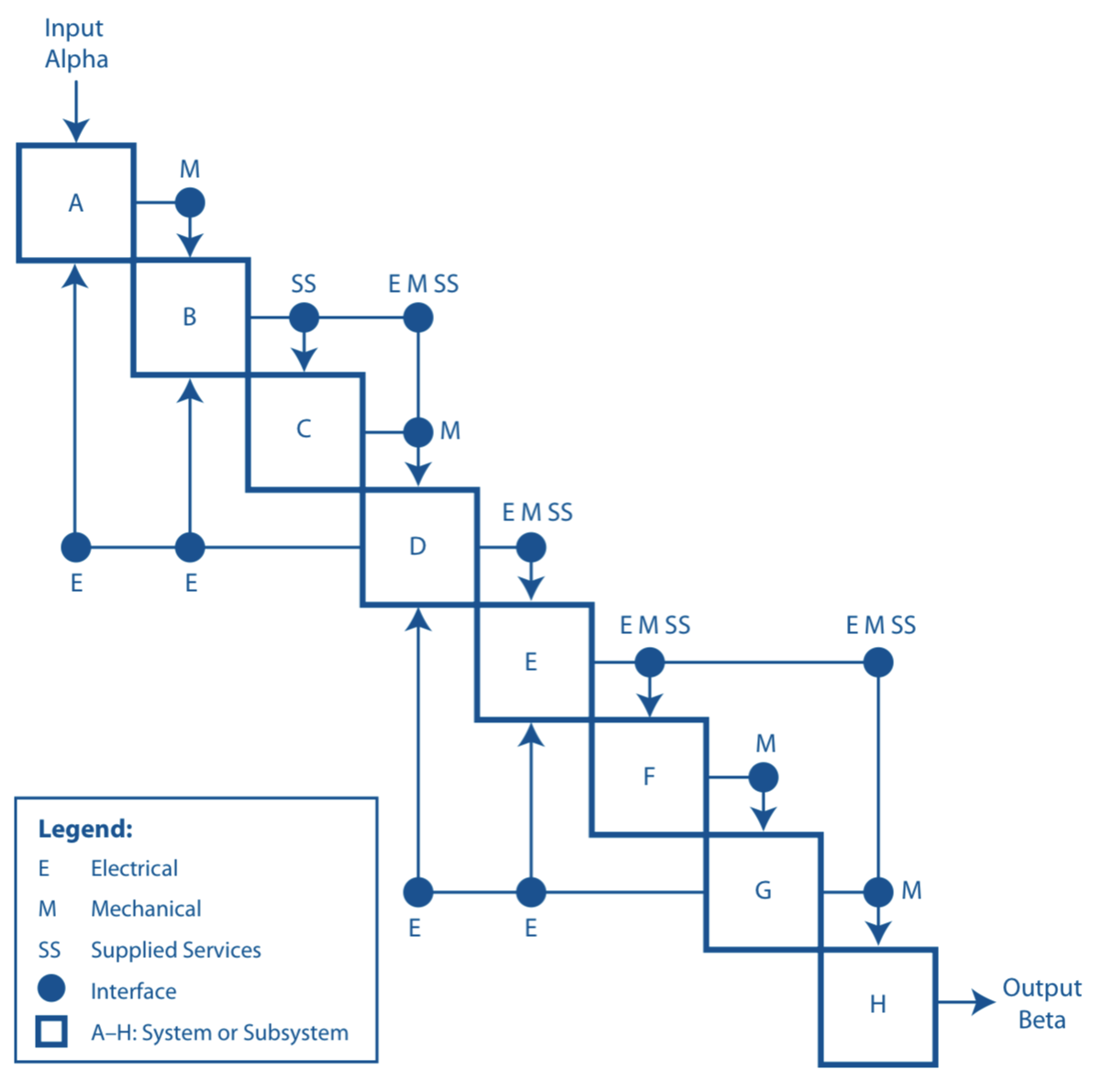

Know All the System-Wide Connections • The system that systems engineers design and manage is a connected network of products and ideas. The value of a system is both what the individual pieces do and what it all adds up to. A key part of maximizing those twin values is understanding all the connections in the network, and having the ability to help team members see those connections.

To understand all the connections in a system NASA recommends creating an “N2 Diagram”, which makes explicit every connection between every component of the system.

Systems engineers also need to know what Gentry Lee calls the “partial derivatives” of everything – they must know what the effect of changing any variable in the system has on the rest of the entire system. Some changes in a system have only a small effect, others have large cascading effects. A good SE needs to be able to know, with a moment’s reflection, the impact of any change to the system, but a great SE does not limit themselves to knowing the “partials” for only the engineering problems. They have to know the “partials” for cost, schedule, human interactions, etc.

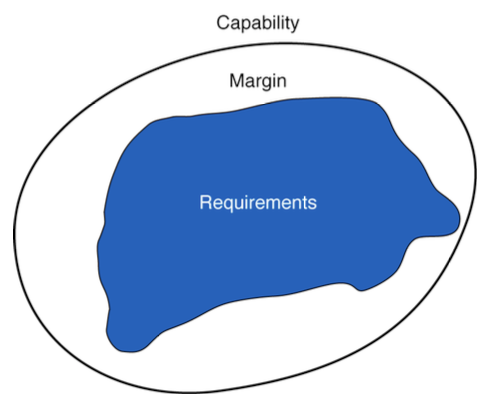

Master of Margins and Reserves • “Good systems engineers maintain a running score of the product’s resources”, but more importantly, they know the difference between requirements and capabilities, and they try to maintain a margin between them. Anywhere that the requirements get too close to the system’s capabilities (where the margin is too narrow) is an area of risk.

The concept of maintaining a schedule or budget margin is universally appreciated, but there are other margins to consider. If the purpose of NASA’s projects is to answer fundamental questions about the universe then a project’s design, from the initial concept phase, should include a “science margin” – the ability to make discoveries and do scientific work beyond the requirements of the mission.

Those excess capabilities wind up being the only things you have to trade as you encounter budget and schedule challenges. If your design – before you confront the challenges of verification, validation, and fabrication – starts out with capabilities that barely meet requirements “you don’t have a viable mission.” The implication is that all projects, as they move through the project life cycle, will face moments of necessary change and compromise. Failing to anticipate this is a failure of system design.

Exceptional communicators • System Engineers must be able to

get out of their offices and communicate well – listen, talk, and write. George Bernard Shaw once stated that England and America are “two countries separated by a common language,” but engineers are separated by their separate languages–even more so since the advent of electronic communications. Systems engineering helps bridge the communication gaps among engineers and managers with consistent terms, processes, and procedures. A key to success is the ability to see, understand, and communicate the big picture, and be effective in helping others develop a big-picture view. [The Art and Science of Systems Engineering]

Strong Team Member and Leader • The basic principles of leadership and being a great team member are widely studied and well understood; there are thousands of books and papers that attempt to distill them. NASA’s behavioral study outlines them as: appreciates/recognizes others, builds team cohesion, understands the human dynamics of a team, creates vision and direction, ensures system integrity, possesses influencing skills, sees situations objectively, coaches and mentors, delegates, ensures resources are available.

Comfortable With Change and Uncertainty • Good systems engineers must understand that change is inevitable. They must also understand how to anticipate it, how it affects their systems, and how to deal with the effects without losing sleep. They should understand that requirements are often incomplete or illusory, and that they might not know when their work will be complete. People who need to know the exact boundaries of their responsibility will have a hard time as a systems engineer. Systems engineers operate using an “interrupt-driven mechanism”, where every day the priorities change as a result of some new challenge.

Has the Proper Amount of Paranoia • Smart engineers are accustomed to being right, and will not hesitate to declare that they have solved a problem. But smart systems engineers must constantly question if the proposed solution actually solves the problem. In particular they must focus their paranoia on “critical sequences”. Critical sequences are things that must be done correctly or the mission ends, such as successfully landing on a planet. Being paranoid about these things pays off.

Science Smart, with Diverse Technical Skills • Systems engineers need to be able to credibly interact with discipline experts. To understand the big picture of a mission one needs to be able to understand what the scientists are trying to achieve, what fundamental questions about the universe are being asked by the project, and why they matter.

Self Confidence, Initiative, and Decisiveness • Systems engineers should be confidently aware of their strengths and limitations and must not shy from either. And they must understand that self confidence is not arrogance.

Systems engineers must have a nearly infinite supply of initiative, they should never need anyone to tell them what to do next. Systems engineers must create momentum and be willing to ruffle feathers and make mistakes. The mistakes they make should be commitment-driven mistakes, never the mistakes stemming from a lack of drive, responsibility, or from negligence. Their mistakes should be those of commission rather than omission. Systems engineers must be comfortable taking on the responsibility for every single aspect of the system. They do not need anyone’s permission to investigate any aspect of the system.

Appreciates the Value of Process • Just as a painter cannot work without a canvas and paint, a systems engineer cannot work without processes. Those who say “I don’t need all that process junk” are just as wrong as those who say “If I know the process then I’m a systems engineer”. Neither is true. A systems engineer who has not mastered process cannot do the job, a systems engineer who knows only process isn’t much better.

Conclusion

Systems Engineering has no shocking secrets and it is not a silver bullet. It is an art and a science; it is the belief that defined ideas, expectations, and requirements matter; that good communication matters; that the design of a solution matters; that a rigorous, predictable process matters; and it is the acknowledgment that, more than anything else, people make the difference between success and failure.

It is not hard to imagine the application of this framework to your own work:

- One person builds the team and is ultimately responsible to management. Another person looks after the cost and schedule. Another designs the actual work of the project and how it will get done.

- Create a solution that takes into account all the client’s expectations. Create an idea of how the solution you create will actually be used to meet those expectations. Plan for how it will be built, tested, and operated.

- Create a breakdown of all the problems that need to be solved to make the system possible. Outline all the component parts and what is required of each, paying attention to how to measure their success and how they integrate with the system.

- Make a big-picture plan and insert key decision points where stakeholders approve of the concept, how it will be built, and how much it will cost.

- Ensure that each part of the system not only does what it is supposed to do but that the sum of all the parts adds up the way you want it to.

- Proactively manage the project’s costs, schedule, etc.

- Think about what behaviors the best people have so you can find, promote, and retain them.

References

- NASA Systems Engineering Handbook (SP-2016-6105 Rev2)

- Expanded Guidance for NASA Systems Engineering. Volume 1: Systems Engineering Practices (SP-2016-6105-SUPPL)

- The Art and Science of Systems Engineering

- Behavioral Competencies of Highly Regarded Systems Engineers at NASA

- NASA Systems Engineering Behavior Study (2008)

- Executive Leadership at NASA: A Behavioral Framework (2010)

- “So You Want to be a Systems Engineer?” Lecture by Gentry Lee

- “Systems Engineering When the Canvas Is Blank” Lecture by Gentry Lee