Systems Engineering for Visual Effects

January 2024

Oliver Taylor

This paper describes Systems Engineering, as practiced by NASA, and explores the application of its principles and techniques to the operation of visual effects (VFX) studios. It discusses challenges in VFX projects, like complexity management and technical/artistic integration, and proposes that VFX studios could improve their engineering and operations by adopting the perspective and methods of Systems Engineering.

Introduction

Considering the scale of NASA’s projects the Systems Engineer’s breadth of responsibilities is astonishing. Systems Engineers supervise and are responsible for all hardware, software, equipment, facilities, personnel, processes, and procedures required by a project. The projects they manage are made up of hundreds of components, teams, and sub-projects. The success of these projects is ultimately determined not by a single component but by how these many components, people, and processes work together.

Systems Engineering is an engineering discipline that focuses on the whole system, how all the component parts work together to form a coherent functional whole that fulfills the mission objectives and requirements.

Visual Effects is a discipline born of the successful collaboration between art and engineering. It is an art whose tools are complex engineering projects in themselves, and it is a engineering discipline whose reason for being is artistic. In the art of VFX everything is an illusion, created with slight-of-hand. It requires spontaneity, intuition, psychological and emotional empathy, and the freedom to experiment and fail. The engineering of VFX is not that different form many engineering fields, it requires patience, rigor, and reliability of equipment, processes, and people.

Visual Effects are built on the successful blending of two very different cultures, skills, and ways of thinking. The fusion between them creates a unique playground for innovation, but also a breeding ground for insidiously difficult problems.

Defining Systems Engineering

The NASA Systems Engineering Handbook says:

Systems engineering is a holistic, integrative discipline, wherein the contributions of structural engineers, electrical engineers, mechanism designers, power engineers, human factors engineers, and many more disciplines are evaluated and balanced, one against another, to produce a coherent whole that is not dominated by the perspective of a single discipline.

In a 2007 Michael D. Griffin, an Administrator at NASA, gave a lecture titled System Engineering and the “Two Cultures” of Engineering, in it he says that science has allowed us to improve what we make far better than simple trial and error because it has “taken engineering beyond artisanship”. We can prove, with science, that one thing works better than another and we can use scientific models to accurately predict what kinds of things might work better than others.

The generation of ideas for what we want to make, however, is a different matter. Notwithstanding recent advancements in Machine Learning, the process of intuitively generating concepts and design ideas for the things we make is a creative process. This creative side of engineering is as much an art as painting, dancing, filmmaking, or any literary work. The difference is not how they are created but the standard by which they are judged. In the Arts it is human aesthetics and opinion that are the test, whereas engineering uses more objective methods.

These are the two cultures he refers to. He says that “designers simply do not think or work in the same way as analysts”, which can lead to a kind of cognitive dissonance. “When it occurs in the context of a complex system development, catastrophe is a likely result.”

This dissonance between design thinking and engineering thinking happens because until designs are realized they can only be measured against models of reality, but models of reality are not reality. The difference between the designer’s model of reality and reality itself creates gaps where unanticipated failure breeds.

Additionally, failure in highly complex systems can happen in so many ways that it can be “unreasonable to expect, other than through the harshest of hindsight, that a particular failure mode might have been or ought to have been anticipated”. According to Griffin, complex systems usually fail not because they do not accomplish their nominal purpose but because of unintended interactions between elements in the system.

Griffin mentions a book called Structures: or, Why Things Don’t Fall Down, by J. E. Gordon, which says that disasters are often “intensely human and intensely political affairs”, and “under the pressure of pride and jealousy and ambition and political rivalry, attention is concentrated on the day-to-day details” thus making big picture judgements impossible, and the “whole thing becomes unstoppable and slides to disaster before one’s eyes.”

Systems Engineers are a link between designs and engineers. They are not designers, but they apply design thinking to engineering problems; they are not engineers but apply engineering thinking to design problems. They work with complex systems and focus on the interactions between system components, and how those interactions effect the system as a whole’s ability to perform its intended purpose. They focus, at all times, on the big picture.

Embracing Systems Engineering

VFX studios are structured like factories. They use pre-made systems of people, tools, and procedures. Projects don’t have to design the tools and workflows they will need from scratch because they use the studio’s existing pipeline. In the language of Systems Engineering this is like providing each project at a studio with a template for its system design.

The defining characteristic of a factory is the use of shared resources. This creates enormous value for the factory through efficiencies – cost savings, profits, optimizations, skills transfer between projects, etc – but this value can only be realized when each project uses a nearly identical system design.

Success at NASA is judged scientifically, and a factory is often judged on efficiency. VFX studios judge projects on efficiency and profitability like any business, but ultimately VFX projects succeed based on clients’ subjective evaluations according to their artistic vision. This means that the success of each VFX project is truly judged against a unique benchmark, even the work is seemingly identical to other projects’.

Thus VFX studios must manage a contradiction: every project must both use identical system designs, to create efficiencies, and must use unique system designs, to address their individual needs.

Structural incentives matter a great deal. What VFX studios are doing is creating an environment in which it is possible to do great work. How they manage projects, what project leaders are allowed and enabled to do, and how the factory’s shared resources are managed creates the quality of that environment. Higher quality environments, on average, output higher quality work. This, in turn, determines the level of talent a VFX studio is able to attract, develop, and retain because talent is generally attracted to studios with great tools, procedures, and resources.

Too often VFX project managers are either prohibited by the studio in which they work from customizing their project’s system design, in the name of efficiency, or it never occurs to them to do so. But just as projects are expected to place wildly different images on the screen they too should be allowed, and enabled, to have wildly different methods of accomplishing their objectives.

To embrace system engineering requires recognizing that a project’s system design is as fundamental to its success as its creative direction.

Management Structures

At NASA, projects are managed by three distinct roles. (1) Project Managers are responsible for building the team and for the overall success of a project, (2) Project Planning & Control is responsible for managing the project’s budget and schedule, and (3) Systems Engineers are responsible for designing and realizing everything required by the project.

A VFX studio’s project and resource management structure is split between four primary roles, and is almost universally identical from studio to studio. It’s roots are in the factory-like nature of the VFX studio and how show business has always operated.

- The VFX Supervisor is responsible for the work meeting the creative and technical requirements.

- The VFX Producer is responsible for keeping the finances, schedule, and resource-allocation on track, and represents the project’s client’s interests in any internal discussions at the VFX studio.

- The various Department Supervisors create the engineering for the project – CG and Comp Supervisors, Pipeline Engineers, etc.

- The various Department Heads manage and supervise the shared resources of the factory, and provide them to projects.

This structure means that the responsibly for designing the project’s system is entirely collaborative, rather than the responsibility of a single person.

The Role Isolation Failure Mode

The specific ways in which any system succeeds or fails are unique to its structure. Simple systems might fail because of a lack of redundancy and robustness, whereas complex systems might fail because of dysfunctional interactions between component parts.

This management structure frequently fails because of something I call Role Isolation. This happens when the VFX Supervisor becomes isolated in the creative aspects of the project and beings to disengage from the project’s logistics and engineering challenges, leaving them to be addressed by the Producer and CG Supervisors. The VFX Producer becomes overwhelmed with adjusting project requirements to keep the client happy, keep the budget in check, and bargaining for resources to confront the fluid interaction between shifting project requirements and engineering challenges and setbacks. And the frequently under-resourced Department Heads struggle to keep up with changing project requirements, failures to anticipate technical challenges, and the inability to create robust engineering designs and processes.

Role Isolation describes what happens when everyone becomes focused on their specialty and no one is left to oversee and manage the project’s system. One might argue that great VFX management teams are defined by their ability to mitigate and overcome role isolation through collaboration but NASA takes no such chances.

Technical Leadership & Systems Management

The Technical Leaders, who design the project’s system, must have broad technical knowledge, great problem-solving skills, high amounts of creativity, persistence, and be able communicators and leaders. Even after the correct system design has been selected, however, there are still many ways in which a project can fail. To prevent those failures the system must be effectively managed. System Managers must apply an approach that is organized, systematic, repeatable, demonstrable, and persistent.

Projects and studios dominated by one or another of these approaches regularly fail. Cultures focused on technical leadership often create systems that suffer from a lack of coordination, are difficult to operate correctly, and wind up too expensive to be useful. Cultures focused on system management often create systems that fail to meet client requirements, are not cost effective, and in which the process becomes an end unto itself.

NASA’s solution to this conflict is to develop the “complete systems engineer”, someone who excels at both the technical leadership and systems management, and give them the authority to design and implement the entirety of the system.

Systems Engineering Management for VFX

To follow NASA’s example at a VFX studio would require the creation of a new project management structure.

A novel project management structure, however, would need to account for the expectations, and interactions with, the VFX studio’s clients. Client-side VFX teams are generally structured similarly to vendor-side VFX teams, with a VFX Supervisor responsible for the project’s creative and technical aspects and a VFX Producer responsible for its finances and logistics. To some extent, client-side supervisors and producers expect vendor-side counterparts. Until such time as client-side VFX teams are organized in a different manner vendor-side management structures must provide a reasonably familiar interface.

To both centralize a VFX project’s system design under a single role, and to account for client-side VFX teams’ expectations, I propose the following:

- A Creative Director would be responsible for exploring, developing, identifying, and articulating client expectations; gathering research materials, creating concept art, etc; aligning the vendor’s artists with client expectations; giving creative notes to the VFX studio’s team; and interfacing with the client-side supervisor on the project’s creative aspects.

- A VFX Systems Engineer would be responsible for the conceptualization, design, and deployment of all hardware, software, equipment, facilities, personnel, processes, and procedures required by the project.

- A Project Manager would responsible for interfacing with the client’s financial and logistical needs; negotiating for the VFX studio’s shared resources; interfacing with outsource vendors; and all other logistical and financial needs that may arise. It may be possible for this role to be an administrative studio role, rather than a project role.

System Design & Development

The Rigid Factory Failure Mode

VFX studios are incredibly complex operations with, typically, pretty thin margins. A more reliable, efficient, predictable, and profitable business is created, as in any factory, though standardization—of inputs and outputs, and of people, roles, and processes. As the factory becomes more and more standardized projects that do not fit within the standardized model are seen as risks and disruptions. As a result, sales people go after work with a specific profile, departments and software are optimized to handle certain kinds of jobs better than others, and up and down the hierarchy of people and processes trade-offs are made that favor the standardized, reliable, predictable, profitable work. Once these optimizations become policy and management controls are put in place to ensure adherence to the factory’s sales/production standards the field of possible projects that the studio is capable of working on narrows considerably.

To put it simply: how you work shapes what you are capable of doing.

The opportunity cost of being a rigid factory—of only being capable of working in one particular way—is incredibly high. First, it makes the studio fragile. When you can only profitably do one kind of work you are vulnerable to the dynamic demands of your clients and the industry. Second, it makes the studio a commodity. The ability to solve unique, difficult, non-standard problems is the primary differentiator between studios competing for business. If a studio operates the same way, with the same roles, and the same inputs and outputs as everyone else, they can only compete on price. Finally, and most importantly, rigid studios invert their most fundamental purpose: instead of creating a process that facilitates artistic expression, the studio has created a process that disallows inefficient artistic possibilities.

But the Rigid Factory problem is larger than any single studio. I will not fully explore this topic here but workflows, roles, and processes are so uniform across the industry a kind of self-imposed regulatory regime has been created where VFX work, industry-wide, is really only done in one way. This creates profound limitations to what studios are capable of, how much that work costs (and thus what can be afforded by paying customers), but importantly, to what people believe is possible. The tail is wagging the dog.

The Rigid Factory Failure Mode is a failure not of process competence (how quickly you can move something through all the steps in the pipeline) but a failure of system design.

System Design Challenges at a VFX Studio

At a VFX studio, the formulation of how a project will work, the development of the project’s enabling technologies, and the arrangements for all a project’s required components and resources is generally a haphazard affair.

First, technology development at a VFX vendor is an ongoing, iterative process that outlasts the coming and going individual projects. This makes it challenging to lock-in the technology that will be used for a project. An artist who used a fire simulation system on their last project might find themselves doing the same work on the next project but with revised tools.

Second, a VFX studio’s output is simply images on a screen. If a well-engineered image and a hastily assembled one look identical the difference is immaterial. VFX studios can and often do deliver work that is slapped together and poorly engineered. This results in inefficient and frustrating project environments.

Third, VFX studios are dynamic environments, with constantly changing personnel, tools, and processes. It is not unusual for projects to endure significant changes to its system design stemming from changes to the studio’s pipeline and personnel.

Fourth, the best engineers are often tasked with addressing critical project failures at the studio (often stemming from poor system design and management), firefighting on one project to the next.

Fifth, VFX projects are typically lengthy and costly, so they often start work while a film or series is still being edited to its final shape. This leads, as one can imagine, to fluid and changing client requirements, which impacts engineering work already underway or completed.

Due to these challenges, many VFX professionals believe that rigorous processes and engineering is not possible and that intelligent improvisation is a more sustainable method of overcoming these inherent challenges. But intelligent improvisation and competent systems management are not mutually exclusive. In any complex engineering environment it is of paramount importance to have both the ability to improvise and be rigorous and exacting.

NASA’s System Design Methods

NASA employs a variety of methods to ensure systems engineers design projects with both technical excellence and exceptional management. While not every one of those methods are applicable to a VFX studio some examples are instructive.

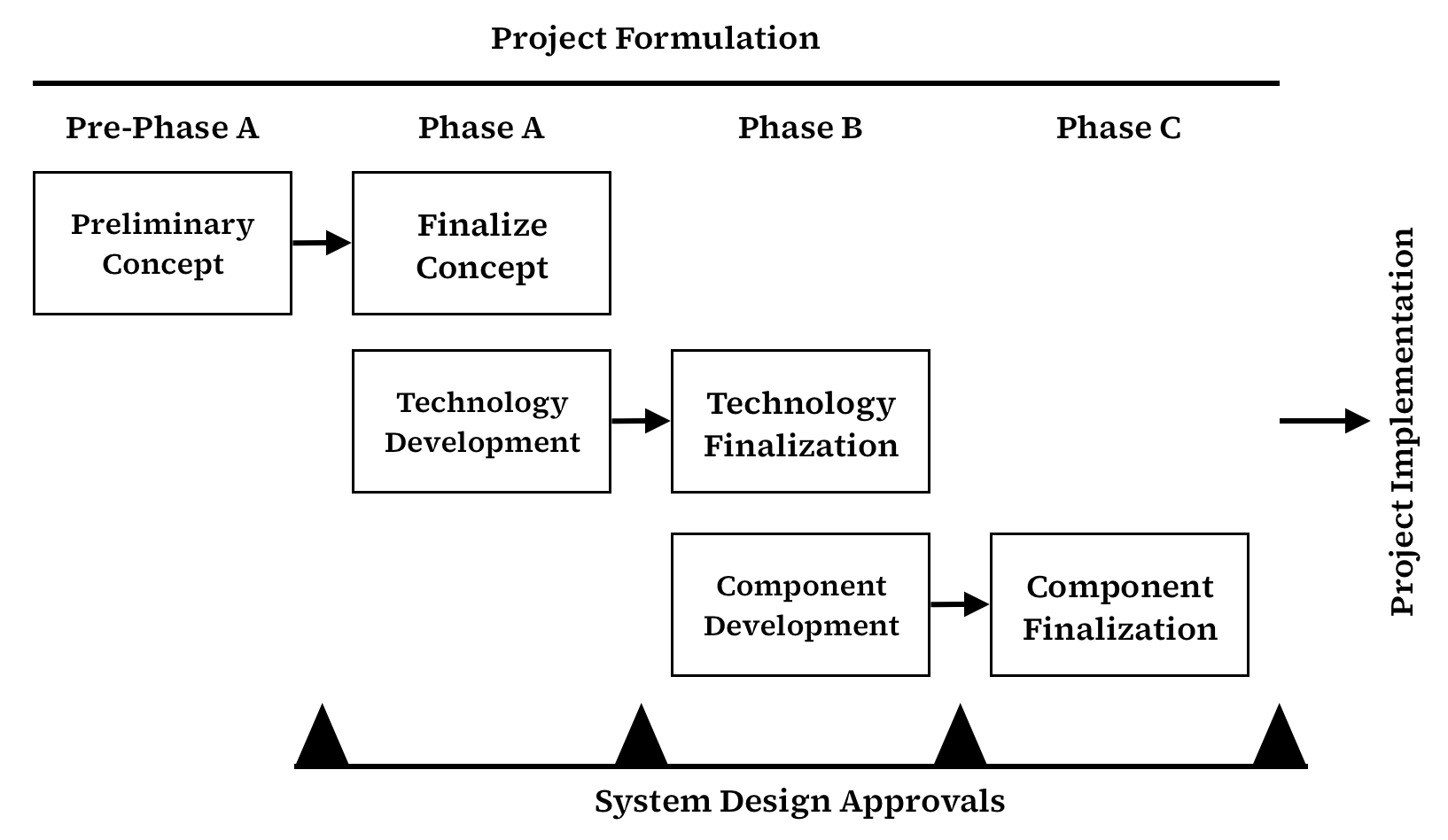

Project Formulation Phases

To formulate a project the systems engineer must conceptualize how the project will work, develop the project’s enabling technologies, and make arrangements for all the project’s required components and resources. Each of these tasks is split into two phases, preliminary and finalization, they are arranged into an overlapping pattern, which are each subject to approval before the project can move forward. This approval process, involving stakeholders, domain experts, and NASA’s administration, is integral to this cycle of project phases. This is done specifically to give NASA better oversight of, and greater insight in to, how projects are being engineered.

The Product Tree

In the language of NASA’s systems engineers, a “product” is anything that must be built for the project. A communications system is a product, but so are all the component parts that make up the communications system. The project itself can be considered a product, comprised of sub-products. System designs are made of “product trees”, which show the dependencies between products and their hierarchy. System design is a process by which project designs are “decomposed” into product trees.

Verification & Validation

These terms have very specific meanings at NASA. Verification is when a product shows “proof of compliance with requirements”. In VFX terms this might mean a CG car asset was built correctly to match a photographed car. Validation is when a product “accomplishes the intended purpose in the intended environment”. In VFX terms this might mean that the CG car is a perfect match for the photographed one when in a fully animated, rendered, and composited shot. This is an important distinction. Products that cannot be validated might meet the initial specifications (verified) but will eventually require redesign and reengineering because they will not work as they are intended to (validated). Redesigns and reengineering often leads to schedule delays and budget overages. The systems engineer’s goal is not just that every component of the system is technically accurate but that the entire system of components effectively work together to meet the project goals. In this way validation acts as a test of each product’s technical specifications.

The Capability Margin

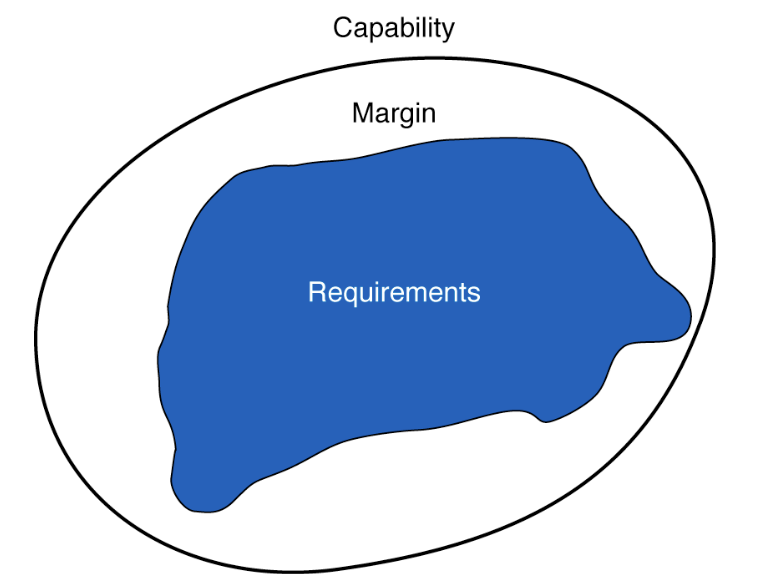

The concept of maintaining a schedule or budget margin is universally appreciated, but there are other margins to consider. At NASA a project’s “science margin” is described as the difference between a system’s scientific capabilities and the project’s requirements. If a project’s system is designed from the start to barely meet project requirements, before you meet the challenges that always occur as a project progresses, then as Gentry Lee (a storied System Engineer) says “you don’t have a viable mission”.

Excess project capabilities are important because they wind up being the only things you can trade as you encounter challenges along the way. The implication is that as projects progress through their various stages they will face moments of necessary change and compromise. Failing to anticipate, and have enough margin to allow for it in your design, this is a failure of system design.

VFX studios that want to take a systems engineering approach to their work might adopt all of these measures. Concepts would be explored and intermittently approved, the system design would be decomposed into a product tree, whose concept and design would be approved by a review board at the studio, components of the system would be regularly tested for both validation and verification, and the entire system would be designed to exceed the required capabilities so that when project requirements change the system remains equipped to fulfill those new requirements.

It would be easy to breeze over this as all being common sense, but the difference between agreeing to this method in principle and actually working this way is vast.

The Concept of Operations

In Systems Engineering a concept of operations, or ConOps, is the plan for how the project’s system will be used once deployed. In the same way concepts document what a project is supposed to accomplish a ConOps documents how the project is supposed to operate.

The ConOps is created after the concepts are approved but before anything is built. It describes (1) the architecture of the system that is being designed, (2) the reason it is designed the way it is, (3) the system’s capabilities and limitations, and (4) how the system will be used by the people using it. This document, together with the project’s concepts and stakeholder expectations, define the requirements for what needs to be built for the project.

It is important to remember that the people using the project’s system are often not involved in constructing it, and as a result they may use the system in unexpected ways. A good ConOps informs that person how the system is designed to be used.

Why Write it Down?

In VFX, documentation is often a dirty word. It is time consuming, a drain on resources, worse than useless given the rapid nature of change, of little near-term value and of only imaginary long-term value, management’s ineffectual way of proving that people are working hard, and most people fear that whatever documentation is created will ultimately become overwhelming and unmaintainable and thus useless. In other words: a waste of time.

This is a shame. Well-written documentation can save your ass. It can create clarity for people new to the project. It can remind everyone what the intent of the various system components are and how they are supposed to work together. It can create transparency for people unfamiliar with the project. It can serve as a useful outline of what the project’s needs are.

Documentation should not be a cumbersome description of things everyone already knows. Documentation should illuminate the reasons why things are done they way they are and make plain and accessible the thought and care that its designers have put into the system design. It should be a place one can go for answers and guidance, it should be a lighthouse when things get confusing.

The ConOps should follow the shape of the project itself. When the project is just a series of conceptual ideas, so too should the CopOps be a sketch. As the project develops and its details become clear, the ConOps should serve as a brief summary of what is taking shape. Only when the project is complete and done will the ConOps be “complete” itself.

But the real value of a ConOps document is that writing clarifies thinking. To quote Paul Graham, writing things down is worthwhile because “good writing is an illusion: what people call good writing is actually good thinking”. He also says “Ideas can feel complete. It’s only when you try to put them into words that you discover they’re not. So if you never subject your ideas to that test, you’ll not only never have fully formed ideas, but also never realize it.”

Writing a ConOps is not the point, the point is to improve your thinking and thus the design of the system. Writing is a very good way to do that.

Aspects of a VFX ConOps

Competent project managers will have a good idea of what to include in project documentation, and there are many things which are obvious: the project’s schedule, it’s goals, technical specifications, etc. but to take a Systems Engineering perspective requires a broader view. The job of a Systems Engineer is to design the whole system of the project, the complex relationships and interactions between parts of the system.

NASA’s Systems Engineering Handbook provides a helpful outline of what kinds of things a ConOps should have. Among the many things that should be included in a VFX ConOps, I would encourage VFX Systems Engineers to include the following.

Client Expectations & Vision

A ConOps should clearly outline client expectations. It shouldn’t simply list dates, numbers of shots, and technical details, it should also outline the the projects artistic goals and all the intangible aspects of the people and systems that might rear their heads at the worst times.

What the System Should Not Be

Just as it is important to define aspirations, it is important to define boundaries. Outlining what the project should not do and what should not be built can help prevent scope creep and over engineered designs.

System Overview & Architecture

A ConOps should describe the architecture of the system, why it is designed the way it is, and the system’s capabilities and limitations. Product trees showing how assets will be built, software dependencies, etc. are very useful. This should be written such that anyone new to the project will find it invaluable for getting up to speed.

How to Use the System

The most important part of a ConOps, in fact its very reason for being, is to describe how the system is to be used to meet the project’s objectives. Diagrams and flowcharts can be invaluable, providing a clear and accessible depiction of complex VFX systems. It should also outline user roles, responsibilities, and the interaction between different stakeholders. The ConOps should translate the system’s technical capabilities into practical operations.

Description of Enabling Technologies

Because the successful use of the system is dependent, by definition, on its enabling technologies some description of them, their operational status, and how to use them is required. Keep in mind that this need not be limited to new technologies, it is anything the project cannot do without.

List of Critical Sequences

In any project there are sequences of actions that must be done, and must be done in a specific order, to prevent catastrophe. For NASA this might mean the things that must happen for a rover to successfully land on the moon rather than explode on its surface. In VFX this might be as simple as a delivery date, but it could be approval of pre-visualization, the integration of assets from third party vendors, or any number of things. Identifying the project’s critical sequences clarifies the parts of the system design that are not flexible and must be protected.

Hardware, Software, and Personnel Requirements

This may sound obvious, but making a list of all the things you’ll need to complete a project, and when you’ll need them, is important. A large part of this is about creating transparency, documentation of what you’ll need and when makes the project’s needs clear to people not familiar with its needs.

Methods of Stakeholder Communication

Completing a project is not just about getting the work done it is also about all the communication that needs to happen along the way. An approval schedule is part of this planning, but so is the methods of communication. Different clients want to be communicated with in different ways. Getting approvals for images over the phone is fundamentally different from looking at the images in person together. These things should be documented so everyone understands how to keep communication on track.

In addition to communication with stakeholders, a project also has internal communication needs. Detailing who needs to know what, who needs to approve what, and when, will help prevent communication and approval bottlenecks as the project progresses.

Risks and Potential Issues

Outlining the risks and potential issues associated with the development and operations of the envisioned system can be very useful. It should also include concerns and risks with the project schedule, staffing support, or engineering approach. Each risk or issue should get a little write-up. Pay special attention to closeout issues at the end of the project.

Project & System Reviews

NASA’s Project Reviews

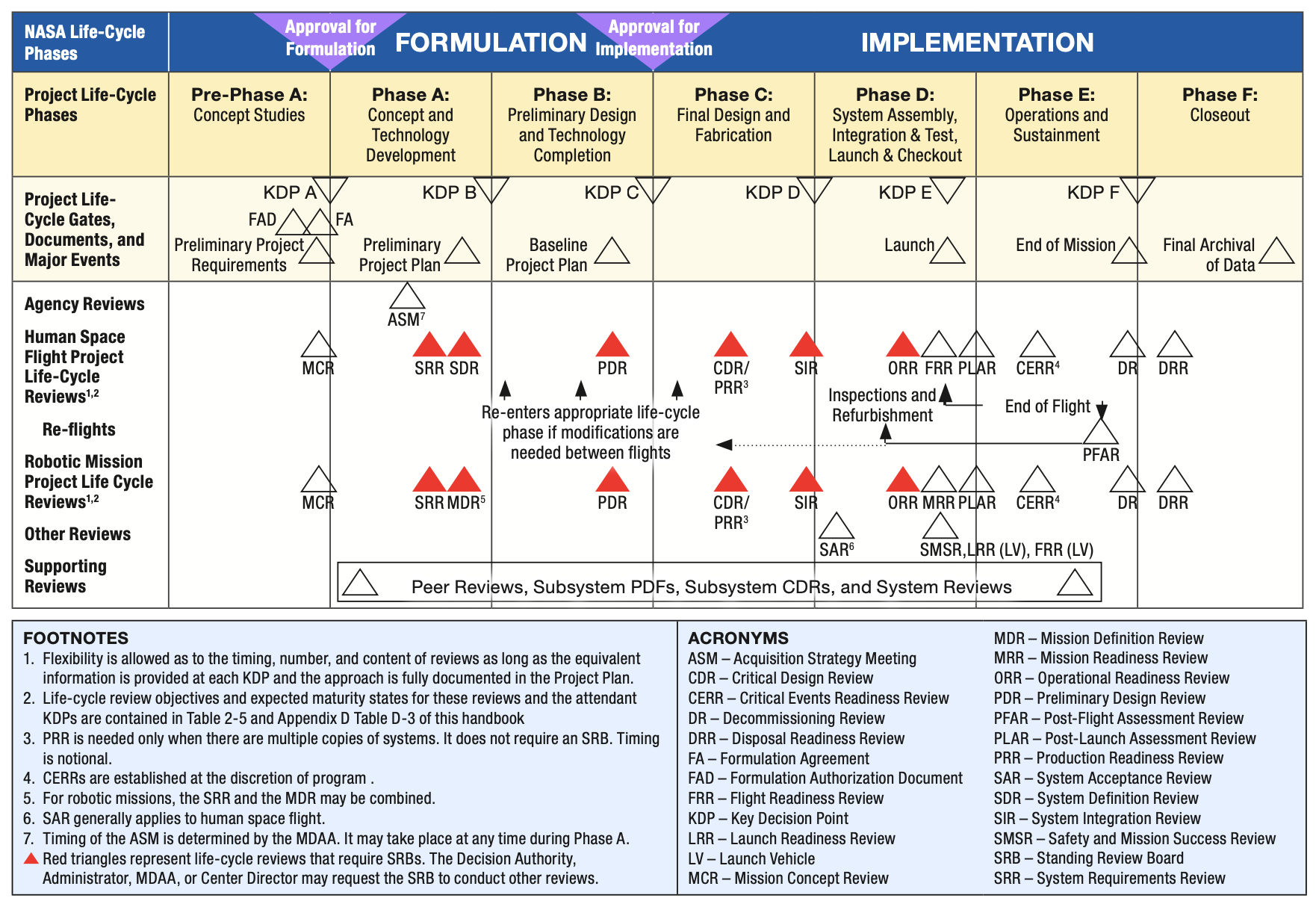

Project phases are designed to organize complex processes into more manageable pieces. At NASA each project phase is separated by a Key Decision Point (KDP). NASA describes KDPs as “the events at which the decision authority determines the readiness of a program/project to progress to the next phase of the life cycle (or to the next KDP).” [NASA Systems Engineering Handbook]

Each phase and KDP is highly structured. The work done in each phase and what each of the KDPs test for are part of official procedure. Part of the reason for this is that the results of these reviews become Federal Records. After all, billions and dollars and people’s lives are at stake. Thankfully this is not the case in VFX.

VFX Project Reviews

VFX projects also have phases and KDPs, but they come in two kinds. Client reviews of the VFX studio’s output, the images on screen, are structured and formal affairs, because the client’s subjective judgment of the work is the project’s measure of success. But clients mostly leave the matter of how the work is engineered and accomplished, up to the VFX studio’s discretion. This means system design and engineering reviews and KDPs are internal matters.

While VFX studios nominally perform internal reviews for system design and engineering, these are largely informal affairs in the form of regular discussions between project teams and the various Heads of Departments, usually focused on solving practical problems.

This is a mistake. If we recognize that a project’s system design is as fundamental to its success as its creative direction then we must subject a project’s system design and engineering to the same level of scrutiny that a client subjects concepts and final renders to. Formal internal reviews provide the VFX studio with the same thing it provides its clients: visibility into the project’s status and process, and opportunities for intervention.

The structure and formality of these reviews is important. Formal presentations establish a sense of accountability and the prospect of professional scrutiny. The idea that our work will be evaluated formally encourages us to better prepare, think more deeply, and pay better attention to detail. They also allow us to gain recognition and positive feedback for good work. This combination of accountability, professionalism, and the chance for positive feedback creates an environment that encourages people to do their best work.

Conclusion

Systems Engineering has no shocking secrets and it is not a silver bullet. It is the belief that defined ideas, expectations, and requirements matter; that good communication matters; that the design of a solution matters; that a rigorous, predictable process matters; and that internal matters like system design and engineering should be taken as seriously as client-facing matters.

This is what I hope VFX Professionals take away from this paper:

- An understanding of what systems engineering is.

- That systems engineering is a way of thinking that anyone, working at any scale, can adopt in their work.

- The knowledge that Systems Engineering was developed expressly to address the challenges of ensuring successful outcomes on some of the most complex engineering projects ever attempted.

- The idea that a rigorous design process and good documentation are worth the effort.

- That there are ways in which existing VFX management structures prevent a holistic and integrated view of VFX projects, and that the lack of this view and management role leads to a common failure mode.

- Some specific, practical system engineering techniques which can be applied to VFX projects.

- The idea that formal and structured internal system design and engineering reviews are as important to a project’s success as client reviews, and should be taken as seriously.

I believe the standard way in which VFX studios manage projects can be improved by adopting some of the practices of systems engineering. I hope that this paper provides some practical guidance on how to do this. And I reject the idea that there is something inherent in the VFX process which makes it’s improvement impossible.

References

To all our great benefit, NASA has extensively written about, lectured, and documented the mindset, techniques, and methods of systems engineering. Anyone interested in more in a more in-depth understanding of the ideas and practices outlined in this paper would do well to explore the references listed below.

- NASA Systems Engineering Handbook (SP-2016-6105 Rev2)

- Expanded Guidance for NASA Systems Engineering. Volume 1: Systems Engineering Practices (SP-2016-6105-SUPPL)

- The Art and Science of Systems Engineering

- Engineering Elegant Systems: Theory of Systems Engineering (TP–20205003644)

- So You Want to be a Systems Engineer?, Lecture by Gentry Lee

- Systems Engineering When the Canvas Is Blank, Lecture by Gentry Lee

- Structures: Or Why Things Don’t Fall Down, by J. E. Gordon — ISBN: 9780306801518

- System Engineering and the ‘Two Cultures’ of Engineering, by Michael D. Griffin

- Complex Systems + Systems Engineering = Complex Systems Engineering, by Russ Abbott