Structured to Innovate

February 2022

Oliver Taylor

Finding a common ethos and project management approach shared by DARPA, Skunk Works, and Bell Labs.

Introduction

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works, and AT&T’s Bell Labs were a few of many R&D organizations that, in the mid 20th century, created technology that helped usher-in the modern world (computers, the internet, communication satellites, digital cameras, etc.). The methods these organizations used in running their organizations also became famous. Despite being very different from each other, they share a similar ethos and approach to project management that teams and organizations of any size (and funding level) can learn from.

This document attempts to summarize that common ethos and project management approach, and create some basic guidance teams and organizations might adopt to follow in these organizations’ footsteps.

DARPA

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is tasked by the Department of Defense with creating breakthrough technologies for national security. Started by the Eisenhower administration in response to the Soviet launch of Sputnik, DARPA’s successes and their impact on the world have been staggering. Moderna’s mRNA vaccines were once a DARPA project, as were weather satellites, GPS, drones, stealth technology, microelectronics, modern robotics, the personal computer, and the internet. Simply put: DARPA’s job is to invent the future.

DARPA’s Key Characteristics

DARPA’s successes are no accident, they are the result of its unique operational and organizational characteristics:

DARPA funds only the most high-risk high-payoff projects, ones that have the potential to lead to transformative technological breakthroughs.

It is idea-driven and outcome-oriented. It does not do “development” (taking mostly proven, if new, technology and developing it so it can be used at scale) nor does it do pure research (research without a clearly defined goal), instead projects are focused on proving that something specific is not impossible, showing that it is possible, and then demonstrating it.

It accepts that most of the projects it funds will not lead to breakthroughs. DARPA funds hundreds of programs every year but only 5-10% of them successfully produce transformative results. DARPA believes that if most of their projects result in success they are simply not trying hard enough (they are, after all, focused on advanced research).

It operates outside the traditional bureaucratic process of the DoD, and operates by special rules and laws created to keep the agency independent, fast, and flexible. There is very little default oversight by Congress or the DoD, and this removes the incentive to go for easy wins and helps their work avoid criticism by external forces.

It does not have its own internal laboratory, instead its projects are executed entirely by universities and private companies. DARPA is, in essence, a funding agency. Because it does not have standing staff to support it can quickly start new projects and quickly end unsuccessful ones. Importantly, universities and small companies who develop new technology in a DARPA program may keep legal title to any inventions developed with federal money.

Successful projects are transitioned to the DoD and the private sector to be developed into operational systems. Considerable effort goes into the transition process itself, often because new technologies often challenge the status quo, but also because DARPA often creates entirely new fields of technology and science.

DARPA is small in size, it has a lean non-bureaucratic structure, a focus on ambitious goals, and highly flexible and adaptive program management.

Organizational Structure

DARPA’s organizational structure is very simple and flat. The Secretary of Defense directly oversees DARPA’s Agency Director, who oversees various “systems offices” (for example the Biotechnologies Office, and Defense Sciences Office, the Microsystems Technology Office, etc.).

Each of these offices fund multiple “programs”, which are managed by program managers (PMs). PMs propose new programs and all their details: their scope, why they should be funded, the objectives, metrics for measuring progress, budget, and schedule. PMs are the judge, jury, and executioners of their own programs. They are expected to bring a vision, select R&D “performers” (companies hired to execute projects within the program), and they can start and end programs very quickly.

PMs are not permanent employees but technical experts contracted for two years with an option to renew. Limiting tenure at DARPA fosters a sense of urgency in PMs to peruse their program’s vision, and for the agency it helps ensure that creativity and productivity remain fluid.

DARPA centers around badass program managers who conceive of, and own, the programs they run—and, critically, they are empowered to make all the program’s most important decisions, rather than a uninvolved manager or committee.

Programs

A typical program will have specific technical objectives 1, a budget of tens of millions of dollars, and will last roughly 3-5 years. Objectives are kept small and focused, but multiple programs can be chained together into “multi-generational” programs that attempt to tackle ideas of a larger scope. PMs can fund smaller “seed” programs—3-9 month projects designed to “move concepts from ‘disbelief’ to ‘mere doubt’”. They can create prize competitions, conferences, etc.

All proposals and programs are evaluated by a “Tech Council” of experts in the program’s area. The tech council has no power of approval over the program, it simply advises the agency director as to the program’s technical soundness. However, their scrutiny is intense. Program managers have described pitches to the tech council as “more difficult than defending my PhD”.

Once approved by the agency director the PM writes a “Broad Agency Announcement” (BAA) that describes the program, the metrics, how companies and universities can propose to the program, how proposals will be evaluated, etc. It takes about 1 month to complete and release a BAA; proposals are due 60 days after. It takes about 2 months for PMs (with a group of technical advisors) to evaluate and award the proposals. In total it takes about 6 months from the Director’s approval of a BAA to when performers can start work on a program. For a government agency this is extremely fast.

DARPA’s programs are designed to prove very specific goals, their technical validity is intensely evaluated, and can be quickly started and quickly ended.

Skunk Works

“Skunk Works” is the official pseudonym for Lockheed Martin’s Advanced Development Programs. It created the United States’ first fighter jet, the U-2 spyplane, the SR-71 Blackbird, the first stealth aircraft, and more. The term “skunkworks” has transcended the aerospace industry and become part of the cultural lexicon—Wikipedia says that “‘skunkworks’ is widely used in business, engineering, and technical fields to describe a group within an organization given a high degree of autonomy and unhampered by bureaucracy, with the task of working on advanced or secret projects.” But to simplify its meaning down to an autonomous group working on a secret project minimizes what makes their way of working powerful.

Skunk Works’ goals are different from DARPA’s. Instead of advanced research they have a very practical objective: turning new technologies into operational aircraft. Despite their differences it is clear that DARPA and Skunk Works share a similar ethos and project management philosophy.

Helpfully, Skunk Works’ founder, Kelly Johnson, created a list of 14 rules they operated by, which I’ve summarized below.

- The Skunk Works manager should be given practically complete control of the program, and should report to a division president or higher.

- Small, but strong, teams should be provided by the military and contractors/vendors.

- The number of people with any connection to the project must be restricted in an almost vicious manner (10% to 25% of so-called normal systems).

- Use a very simple [schematic] drawing and drawing-release system with great flexibility for making changes.

- There must be a minimum number of reports required, but important work must be recorded thoroughly.

- There must be a monthly cost review covering spent and projected costs.

- Contractors should be responsible for ensuring subcontract bids are correct rather than Lockheed.

- Basic inspections should be carried out directly by vendors and subcontractors, rather than Lockheed doing all of it.

- Contractors must be delegated the authority to test their final product in flight, this is useful for them apply lessons learned to future aircraft.

- All hardware specifications must be agreed to well in advance of contracting. Additionally, clearly stating which specifications will not be knowingly followed is highly recommended.

- Payment to contractors must be prompt, contractors shouldn’t have to pay out-of-pocket to support government projects.

- There should be close, daily, collaboration between contractors and project managers to cut correspondence and misunderstanding to a minimum.

- Access to the project, and all its people, must be strictly controlled.

- Instead of paying people based on the number of people they supervise, good performance must be rewarded in other ways.

Bell Labs

For a long stretch of the 20th century, Bell Labs was the most innovative scientific organization in the world. They were largely responsible for: the laser, solar-cells, communications satellites, touch-tone telephones, the transistor, UNIX, the C programming language, digital signal processing (DSP), cellular telephones, data networking, the charge-coupled device (CCD), and a total of 8 Nobel Prizes in Physics.

Bell Labs was very different from both DARPA and Skunk Works—at the time they employed about 15,000 people, including some 1,200 PhDs; they focused on building a large team of talented people and keeping them around for a long time; and 90% of their workforce was focused on development not research—but a closer examination reveals what, by now, are familiar themes:

It had a very flat structure. CEO → President → Directors → everyone else.

The project managers had almost total autonomy over their projects.

It was well run, with managers who typically had strong technical track records of their own, and who appreciated scientific work.

They hired the best people in the world and did everything they could to keep them around: “Rather than letting its org chart dictate its hiring practices—as in, ‘We’d love to hire you, but you don’t have the particular skills we need right now’—Bell Labs prioritized hiring talent, period, even when it wasn’t immediately clear where in the organization that talent would fit.”

They set up satellite facilities in AT&T’s manufacturing plants to better transition the research into development.

[Mervin Kelly’s] fundamental belief was that an “institute of creative technology” like his own needed a “critical mass” of talented people to foster a busy exchange of ideas. But innovation required much more than that. Mr. Kelly was convinced that physical proximity was everything; phone calls alone wouldn’t do. Quite intentionally, Bell Labs housed thinkers and doers [research and development] under one roof. [source]

This unique combination of characteristics and priorities allowed Bell Labs to, like DARPA, focus on high-risk high-payoff ideas that mostly fail but whose successes change the world.

Analysis

DARPA, Skunk Works, and Bell Labs are all very different from each other. DARPA creates hundreds of programs each year, with mostly wild ideas, designed to test specific objectives, using third parties to do all the work, that they can spin-up and wind-down quickly—and only 5-10% meet their objectives. Skunk Works focuses on developing new aerospace technology and actually building operational planes. Bell Labs created a massive stable of brilliant minds and gave them almost free reign to do work that interested them, trusting that brilliant people create brilliant things, which could be harnessed for AT&T’s needs.

Despite their differences, all three organizations share a similar ethos and approach to project management. All three focus on:

- Radical or ambitious ideas.

- Specifically testable objectives.

- A structural dedication to flexibility.

- A rejection of bureaucratic oversight.

- Empowering those running the day-to-day of the projects.

- Allowing wild ideas to fail.

- Putting tremendous effort into making new technology operational.

That might sound obvious, but think about how common the mirror image of an organization like that is:

- A focus on incremental improvements 3 to existing processes.

- With amorphous, shifting, or undefined sets of goals.

- Rigid internal structures and divisions between groups, each with their own set of objectives and needs.

- A project’s ongoing need to justify expenditures and progress.

- Overseen by groups of people not working on the project, and perhaps with no knowledge of the field.

- Applying tremendous pressure to succeed at everything they do.

- Halfhearted roll-outs of new technology and processes.

Advice to Organizations Who Want to Apply These Principals

It is easy to create a small team and tell them to focus on game-changing technology, it is much harder to allow them to fail, to remain flexible, to resist the urge to constantly track their progress and justify their budget, to allow the team itself to make all the major decisions, and to know that once they create something amazing the work has only just begun.

Not every organization can be like these three. Most do not have the same amount of funding, most do not have the resources or ability to focus on world-changing ideas. But organizations of any size can learn from, and perhaps adopt, the common ethos and project management approach shared by DARPA, Skunk Works, and Bell Labs.

Use small teams of talented people, outside a bureaucratic structure.

“The number of people with any connection to the project must be restricted in an almost vicious manner (10% to 25% of so-called normal systems).”

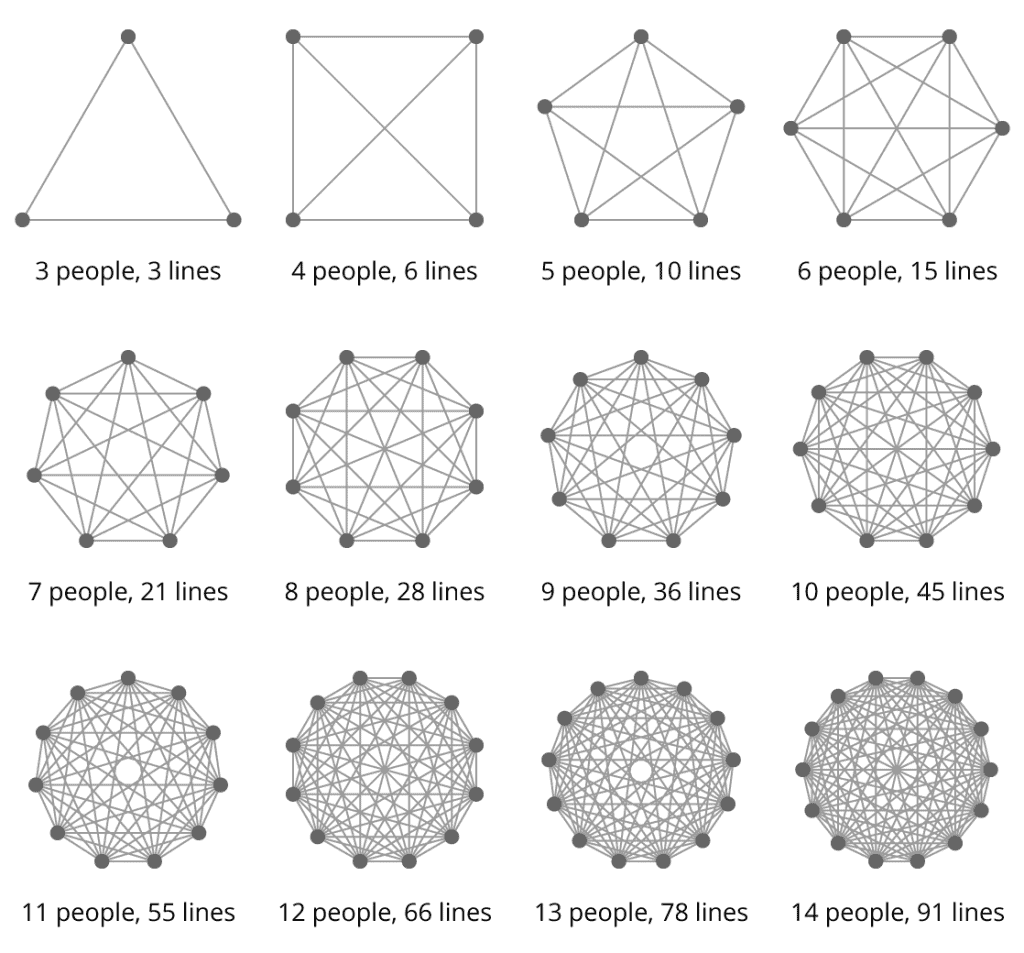

Small teams aren’t better at groundbreaking technology simply because they’re smaller, they’re better because there are fewer lines of communication, they are faster to react, are less expensive to transition to new things, and politics and territorialism are less likely to take root.

Once you’ve decided who your C-suite supervisor will be, there should be no need for more than 2 levels of oversight above the people directly responsible for running the project itself.

Keep them focused on radical ideas, small objectives, and speed.

Design projects to test specific, well-defined (and documented) objectives 1. Consider also emulating DARPA’s “Tech Council” by creating a group of experts, not managers, who advise management on the soundness of the projects.

Setup a funding and management structure that makes creating and terminating projects quick and easy, to better foster the rapid testing of new ideas. The more expensive it is to try something new the less you will do new things.

DARPA’s focus on proving small objectives and combining them into “multi-generational” projects is unique among these companies. And it offers a useful approach, for organizations of any size or budget, that seems to combine the desire for radical ideas and the need to use limited resources.

Empower project managers to make all the project’s most important decisions.

Hire the best people you can and give them almost total control and autonomy over the projects. Project managers should be given the scope to go with their gut and do what they think is right. This removes the incentive to go for easy wins or to avoid objectives and tactics that might attract criticism from outside forces.

Constant oversight is a corrupting influence that forces project managers to evaluate what they are doing through a political or financial lens that often distracts from or degrades a team’s ability to execute a project.

As long as they’re within the parameters of the project’s schedule, budget, and objectives, do not subject them to quotas, deadlines, etc, leave them to the work. 3

Ensure incentives and structure create a sense of ownership at every level.

Just as project managers should be empowered to define their project, run it, and judge its success, participants (the ones doing the actual work) need to take a similar sense of ownership. For example, engineers responsible for writing code should also be responsible for testing it in production, the people who design the aircraft should be there when it is built to understand the challenges of actually making and using the thing.

Allow research to fail, and require that development does not.

Research must be allowed to explore possibilities and find dead-ends. Groundbreaking labs focus on high-risk, high-payoff projects, accepting that most projects will fail to produce results.

Development, on the other hand, targets making a new technology possible to use/produce at scale and focuses on delivering it in a usable form to customers. This often takes far more effort than one might expect—remember that Bell Labs had 90% of its staff on development work, not research.

Endnotes

When designing new programs, PMs use a set of questions written by George Heilmeier (DARPA Director, 1975-77) called “The Heilmeier Catechism” to help articulate why a program is worth doing:

- What are you trying to do? Articulate your objectives using absolutely no jargon.

- How is it done today, and what are the limits of current practice?

- What is new in your approach and why do you think it will be successful?

- Who cares? If you are successful, what difference will it make?

- What are the risks?

- How much will it cost?

- How long will it take?

- What are the mid-term and final “exams” to check for success?

Taking an incremental approach to innovation is not always bad. Apple, for example, is often thought as focused on groundbreaking technology, but their true skill is in iterative improvement:

They take something small, simple, and painstakingly well considered. They ruthlessly cut features to derive the absolute minimum core product they can start with. They polish those features to a shiny intensity. At an anticipated media event, Apple reveals this core product as its Next Big Thing, and explains—no, wait, it simply shows—how painstakingly thoughtful and well designed this core product is. The company releases the product for sale.

Then everyone goes back to Cupertino and rolls. As in, they start with a few tightly packed snowballs and then roll them in more snow to pick up mass until they’ve got a snowman. That’s how Apple builds its platforms. It’s a slow and steady process of continuous iterative improvement—so slow, in fact, that the process is easy to overlook if you’re observing it in real time. Only in hindsight is it obvious just how remarkable Apple’s platform development process is.

Alan Kay, a notable computer scientist, once gave a talk to Disney executives about “new ways to kill the geese that lay the golden eggs”:

set up deadlines and quotas for the eggs. Make the geese into managers. Make the geese go to meetings to justify their diet and day to day processes. Demand golden coins from the geese rather than eggs. Demand platinum rather than gold. Require that the geese make plans and explain just how they will make the eggs that will be laid. Etc.*

Identifying What to Work On

Richard Hamming, a mathematician who spent time at Bell Labs, used to give a lecture titled You and Your Research, in which he said:

each of you has but one life to lead, and it seems to me it is better to do significant things than to just get along through life to its end. […] Thus in a real sense I am preaching the messages that (1) it is worth trying to accomplish the goals you set yourself and (2) it is worth setting yourself high goals.

He believed that “most scientists spend most of their time working on things they believe are not important and are not likely to lead to important things.” He tells this story to highlight the importance of working on important things:

As an example, after I had been eating for some years with the physics table […] I shifted to the chemistry table in another corner of the restaurant. I began by asking what the important problems were in chemistry, then later what important problems they were working on, and finally one day said, “If what you are working on is not important and not likely to lead to important things, then why are you working on it?” After that I was not welcome and had to shift to eating with the engineers! That was in the spring, and in the fall one of the chemists stopped me in the hall and said, “What you said caused me to think for the whole summer about what the important problems are in my field, and while I have not changed my research it was well worth the effort.” I thanked him and went on—and noticed in a few months he was made head of the group. About ten years ago I saw he became a member of the National Academy of Engineering. No other person at the table did I ever hear of, and no other person was capable of responding to the question I had asked: “Why are you not working on and thinking about the important problems in your area?” If you do not work on important problems, then it is obvious you have little chance of doing important things.

We should all spend less time working on things we know are not important and will not lead to important things, and more time working on what matters to us, the things that will solve the biggest problems we have. Any organization who wants to emulate these three would do well to start with Hamming’s question.

References

It should be noted, very clearly, that my analysis of these organizations should not be considered an original work, but rather a summary derived from other sources:

- Why Does DARPA Work?, by Ben Reinhardt

- The DARPA Model for Transformative Technologies, by William B Bonvillian, Richard Van Atta, and Patrick Windham

- The Idea Factory: Bell Labs and the Great Age of American Innovation, by Jon Gertner

- What Made Bell Labs Special, by Andrew Gelman.

- A growing number of governments hope to clone America’s DARPA, The Economist

- Principles for Innovation Orgs, by Ben Reinhardt